- D-Day Dakota

- Lost and Found

- Low and Fast

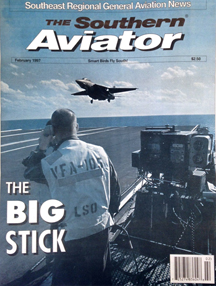

- The Big Stick

- True Confessions

THE paratroopers huddled, shoulder to shoulder, on the cold steel floor of the Dakota as the throaty roar of its big radial engines reverberated through the open jump door.

No one even tried to talk above the din. It was noisy, confusing even, but that wasn't the reason for the silence. Each man was alone with his own thoughts. They were here now, preparing to hurtle out of the C-47 and into the sky above a foreign land. They had been swept along this course, destined to participate in events bigger than themselves — to become part of history. Nevertheless, although the time had come to jump together, each man was alone.

It was time. They stood up with resolve, snapping their rip cords onto the static line. They moved through equipment checks, following by rote and practice each move that would lead them to the small jump door.

Quickly, almost suddenly, each reached out in turn to grip the door frame and, looking back over their shoulders, waited for the jumpmasters’ command: “Go!” Six seconds pass. “Go!” And again, until each man in the stick was away.

Below, the Normandy countryside was a patchwork of hedgerows around the small village of Sainte-Mére-Ere-Eglise. The date was June 5, and the eyes of the world were watching.

———

This June 5 came 50 years after these same men first jumped from a Dakota over the Cotentin peninsula. During that first fateful leap in 1944, they jumped under cover of darkness into a nightmare of war and death. They lost their buddies, their comrades — and they lost their youth.

Now, in 1994, they returned to Normandy to jump again, to honor their fallen comrades and their own places in history. Forty-one veteran World War II paratroopers, 20 of them actual veterans of D-Day, fulfilled their destiny. They came back to repeat the jump they’d made as boys. These men, all between the ages of 68 and 84, had overcome resistance from their own government and the government of those they liberated 50 years before.

When the jump finally went off on June 5, the world watched as their heroic story was told. But the Dakota that flew them, which brought back pungent memories of a half-century ago, also has a story — for it is also a veteran of that longest day. The effort of flying it back to Normandy was itself heroic.

This is the story of that C-47A and its return to Normandy: the D-Day Dakota.

———

DON Brooks has been there and done that. The auto parts distributor from Douglas, Ga., has a knack for making big dreams come to life.

When Pat Epps launched his quest to dig P-38s out of the Greenland icecap, Don Brooks was the guy who brought the big ride. The workhorse of the Greenland Expedition Society was N99FS, a C-47A that was converted to a DC-3 by Basler Flight Services in Oshkosh, Wis., back in 1986. Familiar to thousands of pilots who have seen it at Oshkosh or Sun 'n Fun, the big red Gooney Bird with its massive skis has carved its own special place in aviation lore. Flying in and out of Kulusuk, Greenland, it ferried men and supplies to the icebound work site without malice.

Brooks, to make sure it was always ready, coerced an irascible Bob Harless into the dual roles of chief pilot and head knucklebuster. Harless, an encyclopedic aviation raconteur, operates Harless Aviation, the FBO at Douglas. Bob has a wallet full of official-looking FAA documents for taking care of airplanes. A&P. I-A. Designated Mechanic Examiner. And while most airplane mechanics have the good sense not to fly, Harless is the most feared Designated Pilot Examiner between Live Oak and Waycross.

He also just happened to fly and maintain DC-3s for the old Southern Airways. He is part Gooney Bird.

———

Epps, Brooks, and Harless. Kind of the Manny, Moe, and Jack of aviation adventure hereabouts.

So Brooks says to Harless, sitting under the shady Dakota wing at an Augusta airshow, "Let's take this thing to D-Day."

Harless thinks Brooks is crazy. D-Day isn't a month off.

"We probably ought to do something about that right engine," Harless tells Brooks.

"Aw, it only has to run for a hundred hours for that trip. It can make it a hundred hours." Brooks claims.

Then Brooks calls Epps. Epps is in.

Harless, he's in trouble.

———

IN less than three weeks, Brooks and Harless faced the task of transforming the big red DC-3 into a nostalgic C-47. Liveried in the olive drab of wartime, the airplane was recast as KG395 — a Dakota of the Royal Air Force Transport Command's 46th Group, 48 Squadron, the unit it served on D-Day. Ed Davies supplied Harless with accurate schemes, and the paint was still drying when the plane left for Normandy.

Sitting on the ramp at Epps Aviation in Atlanta, juxtaposed against business jets, the Dakota was resplendent in its invasion stripes — swaths of black and white bands around its wings and fuselage. Every aircraft flying on D-Day was painted with invasion stripes, allowing fighters overhead and gunners below to identify friendly aircraft with ease.

Using a set of 1944 shop drawings procured from Lockheed, Harless installed the jump static line inside the cabin to original military specifications.

And Harless installed one new item in the Dakota's panel: a new GPS receiver.

———

By the time Brooks called me, there was only about a week left to prepare for the trip. Going along were Brooks, Harless, and Epps, plus Joey Hand, Dr. Dan Callahan, and Ramsey "Bub" Way. We would also have a German television camera crew aboard, recording the trip for a Speigel TV documentary.Completing our entourage was Ed Davies, 60, from Millbrae, Calif., an aviation writer and DC-3 historian. Ed had crafted a long history of our Dakota for Flypast magazine in England, and was enthralled with being part of the mission. Though he knew every detail of the airplane's history, this was the first time he had seen it.

Joey Hand, 37, is a multi-engine, instrument-rated pilot from Douglas. A long-time friend of Harless and Brooks, he had been to the icecap with the Greenland Expedition. I first met him in Kulusuk, when he was leaving and I was arriving. We shared a snowy walked to an Eskimo village together.

The next time I saw him was on the ramp at Douglas. "We've got to stop meeting like this," I told him.

Hand knows his way around the DC-3, having helped Harless ready the airplane for various journeys over the years. Having him along would prove crucial.

Dan Callahan, 70, or "Dr. Dan," is a mostly-retired family practice physician from Macon, Ga. One of the principals in the Greenland Expedition Society, he’s also very active in the Air Force Association — where he serves as southeastern regional vice president. Dr. Dan was a medical technician in the Pacific Theater during WWII and he served as the flight surgeon for the Greenland expeditions. On our trip to Europe he’d have occasion to pull out his black doctor's bag and issue some potion or salve to several of us.

Having Dr. Dan on the trip was great — you didn't need an appointment or an insurance card.

Ramsey "Bub" Way, 60, owns an automobile dealership in Hawkinsville, Ga. He had also been a fixture on trips to the icecap to recover the Lost Squadron P-38. He was one of the few humans who made the long trip down into the 264-foot hole, tethered to the end of a chain hoist. I had done that, too, so without knowing anything else about him, I figured him at least as crazy as the rest of these guys.

———

You've read those long stories in aviation magazines detailing the trials and tribulations of ferry pilots who brave the North Atlantic to shepherd their craft to Europe. You know about the complicated logistical planning for such flights, figuring fuel burns and installing ferry tanks. Survival techniques and mastery over the weather. Countless hours spent carefully checking routes and stuff like that. Right?

Epps doesn't do it quite that way. The extent of his planning is asking his patient wife Ann to ensure he has some extra underwear. He flies to Greenland like most people go down to the market for a gallon of milk.

The day we left, he was working in his corner office, which overlooks the runways at DeKalb-Peachtree Airport. When it got dark, it dawned on him that he needed to pack.

Ann packed his clothes, I'm sure, because all Pat thought to bring was his bicycle.

———

WITH the passenger manifest set we were all assembled in Atlanta, scurrying around to take care of last-minute details. My friend Bob Minter of Nashville was in Atlanta on business, and he stuck around until late in the evening to see us off. He hauled me to a grocery store, where I stocked up on critical items like Oreos and Snapple. Everyone brought food, and like an airborne smorgasbord, we had boxes of stuff to eat and drink on the long flights.Finally, at 1:45 a.m., we closed the doors and rumbled down runway 2 at PDK. Next stop: Quebec City, Canada.

During the seven-hour flight to Quebec, the heated cockpit provided the only warmth in the airplane. Joey Hand managed to curl up his large frame on the floor while Harless, slightly built, contorted his lanky limbs into the cramped navigator's seat and tired to doze.

The Dakota droned on. Epps, flying from the left seat, actually seemed to be part of the equipment rather than its manipulator.

In the back of the cold cargo hold, six old airline seats had been secured to the floor tracks. The others had fallen into restless sleep, already exhausted from the long day of preparation.

The airplane sailed at 7,000 feet, churning along through the clouds of a cold front over the Northeast. Brooks, in the right seat, spoke over the intercom to Epps: "How cold do you think it is out there?"

"Warm," Epps drawled, a moment later pondering. “Don’t you think it's warm?"

And a few seconds later he added, "Keep an eye out there for ice."

Don looked over at him and dryly responded, "If I start talking like Barney Fife, there's ice."

On through the front and into a brilliant dawn, the sunrise poured a soft light over the invasion strips on the Dakota's wings. Below us, the St. Lawrence Seaway arced across our path as we descended to land at Quebec.

———

Notorious for oil leaks, big radials like the Dakota's Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasps often leave pools of fluid beneath their cowls. On the ground at Quebec, Harless seemed concerned. There was a lot of oil, more than normal, and it was all over the right engine and gear well.

After some tinkering and figuring, he and Hand set about removing the entire right engine cowling to get a better look. Working out of a red toolbox, they took on the profiles of shade tree mechanics on the ramp of Quebec's government hangars.

Five hours later, it was decided that the leaks were under control and we could still make Goose Bay, four hours north. The weather had been good over the north that day, and Epps had hoped to push on to Greenland. The long delay at Quebec nixed that goal, so a night at Goose Bay would be in order.

———

I had been to Greenland before with these yahoos, so I had an idea of what to expect. I had gone out and bought some more Arctic gear, for the ride north in the Dakota’s cargo bay would be frigid.

The ride was noisy, and the wind blew in from under the edges of the cargo door. We used heavy gray duct tape to seal the door and keep the freezing air out. Still, at 9,000 feet the temperature inside the cabin would dip as low as zero degrees Fahrenheit.

Layers of clothes and a wool blanket made the ride bearable. I fashioned a bed atop the netted cargo that took up the length of the cabin and tried to sleep.

Back in Douglas, knowing “if ya gotta go, ya gotta go,” I’d constructed a temporary john from a large, round planter. I attached a toilet seat and used kitchen trash bags to complete the sanitary system. Somehow, through good planning or sheer determination, none of us had to brave the cold in an effort to use my handsome can.

A five-gallon container with a large funnel provided us a relief tube.

All the comforts of home.

———

Brooks stepped into the cabin and knelt to peer out the window at the right engine. I raised up off the cargo bundle to see him grimace. The engine cowl had a growing stream of oil spilling into the slipstream. In a few minutes, the whole cowling would be blanketed in oil. Oil from the engine. Engine oil.

With 170 miles until Goose bay, an uneasy concern pervaded the aircraft. Up front, Epps and Harless had pulled on their shoulder harnesses. Cold and shivering, Hand sat by the window, watching for smoke or fire. In the rear, the rest of us sat pensively. It would be a long hour and a half.

Below, there was absolutely nowhere for a Gooney Bird to land among the rocky crags and wooded hills of the inhospitable Labrador coast.

"Do you want to land in the rocks or one of those lakes?" Epps asked Harless.

"Pat, I want to land at Goose Bay," Harless said stoically.

———

THE entire base fire brigade welcomed us at Goose Bay. There was no fire — in fact, the sturdy radial engine continued to develop power and hold oil pressure, even though one cylinder had blown and another was cracked.We crowded under the engine, which was unceremoniously covered in oil, to inspect the damage and congratulate ourselves on living through the ordeal.

Harless pulled himself up on the front of the cowling to peer into the engine and saw the cracked jug. It had broken the prop control cable bracket, which could have presented real problems if we’d had to feather the prop.

We left the airplane on the ramp and warmed up inside at Woodard Aviation Services, the FBO at Goose Bay. Murray Pike, the manager, would provide us with tremendous help over the next few days.

———

That night at dinner, we did what any group of pilots in such a situation should: Drank scotch.I had the foresight to bring along a fifth of Johnnie Walker Black Label. We poured shots from the bottle and raised a toast to Epps and Harless.

Thoughts of taking the airplane over the ocean were on our minds, but there was outward determination to continue. Going back now was not an option.

"We have a mission to complete, and that's what we're going to do," Brooks said. "We're expected. Folks are waiting for us."

With that said, the task of repairing or replacing the engine became our focus.

———

Epps called Warren Basler. Basler Flight Services, Inc., is known for its specialty DC-3 renovations. They had rebuilt Brooks' plane in 1986, converting it from a C-47A to a DC-3. They knew the airplane as “Big Red,” for its distinctive paint scheme when it flew with the Greenland Expedition.Basler told Epps that they kept a couple of engines on hand for use ferrying in DC-3s from around the world. These spares, called QECs or Quick Engine Changes, were already built up with wiring, hoses, and accessories. In theory, you simply unbolt the bad engine from its mounts and stick the QEC in its place, tighten a few hoses and off you fly.

As fate — or just dumb luck — would have it, Basler happened to have one of his turbine conversion DC-3s in Oshkosh, scheduled to fly to Germany. Incredibly, the plane would be leaving for Goose Bay within hours of Epps' call. Basler would put an engine in the turbine DC-3 and it would be delivered to us at Goose. We would have a good engine for the Dakota in a matter of hours.

By the time the Basler turbine rolled out on Runway 6 around 11 p.m., a cold rain was beginning to fall. In sharp contrast to our 140-knot groundspeed on the way to Goose Bay, Basler pilot Dan Reid tracked better than 300 knots in the turbine Gooney.

———

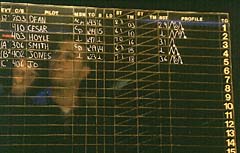

GOOSE Bay has been a waypoint for aircraft crossing the Atlantic for many decades. The United States Air Force maintained a large base there until 1992, when the war reserve of fuel was largely burned away during Desert Storm.Since that time, it has become a training facility for NATO operations hosted by the Canadian Air Force. Contingents from several air forces maintain a presence for the base's NATO mission of training fighter pilots to fly low-level, high-speed flights. While we were at Goose, the German Luftwaffe had a squadron each of F-4 Phantoms and Tornados, the Royal Air Force had two squadrons of Tornados and Jaguars, and the Dutch were flying F-16s. All day long, the base rang with the tremendous noise of fighters taking off and returning.

———

The Royal Air Force allowed us to use one of their large heated hangars, a real plus in the 35-knot wind that was raking the ramp. The airplane, after all, was wearing its original R.A.F. colors.R.A.F. Hangar 6 at Goose Bay looms like a concrete dinosaur over the vast ramp. Great doors grudgingly lumber on their tracks, slowly revealing a cavernous space four or five stories tall and a couple-hundred feet long and deep. British airmen and technicians go about their daily tasks of maintaining fighters and supplies for the outpost.

With no tug equipped to move the Dakota, Harless and Hand struggled to steer the tailwheel with a 20-foot-long steel tow bar. The sight of the Dakota trundling along the taxiway, with grown men chasing after it in an attempt to herd it along, must have appeared comical to the Luftwaffe F-4 pilots rolling past to their ramp.

When the Basler turbine pulled up to the hangar the next morning, Joey Hand deftly maneuvered a large forklift into position, and after a few minutes of cautious finagling, the replacement engine was sitting next to the C-47. The task of accomplishing the engine change was ready to begin in earnest.

Harless and Brooks exchanged grimaces as they looked over the new radial powerplant. The QEC engine had higher time on it than Harless expected and, as would normally be the case, many of the fittings and accessories needed to be changed or altered to work on our Dakota. The back end had some broken connectors and wires, and there were a few other differences that would require extra effort to prepare the engine for hanging on the right wing.

For the next four days, the big hangar would be our home while Harless, Hand, and Brooks struggled to overcome the challenge of replacing an engine with minimal equipment.

Everyone pitched in to help where they could. Doc Callahan became proficient at spreading and shoveling oil-dry. Davies and I became scroungers, visiting tool sheds and mechanic's bays in the RAF and Luftwaffe hangars to find screws and bolts and knick-knack parts for Harless. Bub Way went to work with a wrench to disassemble hoses and accessories from the old engine.

———

When the work was finally finished, the weather over Greenland had deteriorated. Pat made several trips to the Canadian Forces Weather Office and called contacts in Narsarsuaq, Greenland, to get first-hand reports. All of our possible landing sites in Greenland — Godthab, Sonde Stromfjord, and Narsarsuaq — were marginal, with low ceilings and high winds. The threat of icing was great. When the weather failed to improve over several hours, he decided to wait.Here, his experience flying to Greenland over the last 10 years shone through. While other ferry pilots were agonizing about the conditions, Epps had gone to sleep. Conditions did not need to be perfect for him, though.

"If you wait for it to be perfect up here, you'll never go anywhere," he observed. But if conditions were bad, they were bad enough to stay put and wait a bit.

It worked out, for everyone was tired and Harless was a zombie. He slept most of the day, arising now and then only to eat.

———

AT 4:30 a.m., Epps popped out of bed like hot toast. At this time of year this far north, the sun was already up, brightly shining through a crystal-clear sky. The nasty cold overcasts had evaporated over Narsarsuaq, a site known during WWII as BW-1.We filled a couple of thermos bottles with steaming coffee, cranked the engines, and took off, glad to be on our way. Epps turned northeast, flying low along the banks of the Churchill River to give the good folks of Goose Bay-Happy Valley a fond farewell.

The new engine hummed, and each mile raised our confidence and spirits. With favorable winds blowing us along, the Dakota made 180 knots groundspeed, shortening the trip Narsarsuaq to four hours.

Pat flew 50 miles up a fjord to the airfield, buzzing along at a couple hundred feet. The clarity of the air in Greenland gives everything below a vivid color. Ice floes and small icebergs floated in the fjord’s dark blue water. Waterfalls cascaded into the river below from stark, rocky cliffs that lined its banks. Now and again, a single house or a small isolated village clung to low, flat ground near the water.

The scenery is great going into Narsarsuaq for a landing. But the thrill fades quickly if you're paying the gas bill for a C-47. One hour and $4,000 worth of $8-per-gallon avgas later, we were climbing out of the airstrip, flying up a glacier to gain altitude for the flight to Reykjavik, Iceland.

———

We had hoped to fly farther north to Kulusuk, the staging center for the Greenland Expedition's operations on the icecap. Brooks had stowed away some international contraband — 2,000 rounds of 7 mm ammunition smuggled in an ice cooler — for local friends in Kulusuk who needed it for hunting. Since we weren't going to make it, the Commissioner of Civil Aviation in Narsarsuaq agreed to deliver it for us.———

Reykjavik, Iceland, is a terrific, modern city. The people are friendly and engaging, speak English, and like Americans.We were met on the ramp by Gunnar Thorsteinsson, an official with the Iceland Civil Aviation Administration. Gunnar had arranged accommodations for us at the Loftleider Hotel and had the local media out in force to greet us. A long day of flying was rewarded with fine Icelandic fish for dinner and a welcome night of rest.

The next morning we made the four-hour hop down to Glasgow, Scotland, where we landed for fuel and to clear British customs. We had touched down in our fourth country and, so far, hadn't shown our passports to anyone.

———

During the long flights across the Atlantic, Epps and Harless would leave their seats to relax or doze. I took advantage of the opportunity to fly the Dakota for an hour or so at a time. I'm not sure how much DC-3 time goes for, but I sure enjoyed my five or six hours’ worth. Even flying the thing straight and level, following a heading, was huge fun. It flies big and heavy, but friendly.On the way to Glasgow, I was flying when it was time to give a position report. Standard procedure on international overwater flights, the position report is used in non-radar environments.

Its standard sequence is position, time, altitude, estimated time over the next fix and then the following fix. At 9,000 feet, I could not raise Iceland control on the radio, so I simply broadcast. "Any station or aircraft hearing this transmission, respond," I keyed.

An airliner tens of thousands of feet above answered, and passed our report on to Iceland.

Below, the ocean bent away in all directions.

———

BY seven o'clock that night, we were sitting in the pub of the Babbity Bowster, a quaint inn Epps knew in Glasgow's Merchant City district. The apparent proprietor wore an eye patch, and the waitress was a cherry redhead by the name of Judy. After several quick Scotches and at least a few pints of the local bitters, we were getting into our cups and celebrating the successful crossing.Brooks looked over at me and said, "Before we started, you asked me how dangerous it would be." Then, releasing a relieved belly laugh, he continued. "It's real damn dangerous, that's how dangerous."

The Babbity Bowster provided a good night's sleep. The next morning we loaded up and flew to R.A.F. Mildenhall north of London to collect information on our flights to France. We had been expected at Mildenhall several days earlier to take part in a grand airshow, but the blown engine made us miss it.

Instead, we headed on down to Duxford for a couple of days.

———

Steven Gray is an Englishman who has preserved the history of WWII fighters like no one else. His operation, called The Fighter Collection, is located in a WWII hangar at Duxford. The Duxford aerodrome is home to the Imperial War Museum's aviation collection, which is housed alongside the famous turf runways where Spitfires rose to meet the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. Now the museum, along with Gray's collection, is an immensely popular attraction where daily flights of vintage fighters thrill visitors.Gray's collection sports one of just about every fighter of WWII. Spitfires, Hurricanes, Mustangs. He has a Wildcat, a Hellcat, and a Bearcat, along with a Sea Fury, P-38, P-40, and others. All of the airplanes are flown regularly, performing spontaneous daredevilry over the museum grounds.

Gray met us when we landed and arranged accommodations for our crew at nearby Cambridge. Harless was quickly becoming adept at finding pubs, and he landed us at one called The Eagle. The pub is famous for its back room, where its ceiling still bears the imprint of young airmen 50 years past. They would come in at night to drink and relax, and somehow started a tradition of using candles or lighters to inscribe the names of their squadrons on the pub ceiling. Their missives are still plain to read today, and gave a ghostly quality to the evening's banter.

———

ON June 3 we were scheduled to fly to Caen, France, for a rehearsal flight over the Sainte-Marie-Eglise drop zone. Pat had jumped through several hoops during the day to ensure the flight went off. He had to get permission for an early take-off from air traffic control at Duxford; we’d have to be wheels-up by 6 a.m. to make our arrival time of 9 a.m. local at Caen. He had filed a flight plan with Stansted Airport ATC, and everything looked hunky-dory.But the saga of our group's efforts to get the Dakota to France was not yet over. Late that night, after another good evening of food and several more pints of bitters, an ominous note had been slipped under our hotel room door.

Stansted had received a telex from Caen. Our flight plan had been turned away.

"This message from Caen this evening following refusal to accept your flight despite a signal from us stating that your flight was connected with the D-Day ceremonies."

"Madame LeMardis, director of Caen Airport, confirms that we cannot accept N99FS tomorrow, as the authorization has not been requested yesterday or before."

The note said we could call her after 7 a.m. the next day, too late to meet our Air Force contacts.

Epps was irritated. "The whole thing about so much security is ridiculous," he muttered.

Brooks wasn't happy either. "I'm not surprised. There are a lot of people that didn't want the jump to happen all along. I expected some sort of red tape to show up," he muttered. "But we could have quit any number of times. We just won't quit now."

Epps remembered that he had not included our Air Force-issued call sign — Victory — in our flight plan, nor our diplomatic code. He called Stansted back, and asked them to refile with the missing information. The plan was still on to take off, and hope that in the morning something good would happen in Caen.

Eisenhower, it seemed, had less trouble getting to Normandy than we did.

———

Crossing the English Channel the next day was unforgettable. Flying over the white cliffs of Dover, I imagined how the scene below would have looked 50 years ago. Just a few short minutes ahead lay the Normandy coastline, and I pondered how it would’ve felt to be in this airplane on a fateful ride into combat.We crossed the coast and looked down on Utah Beach and the green fields beyond. It was a peaceful patchwork of farms and small villages. How did it look in June 1944?

We reached Caen to find it an airport besieged by an international military machine. Several air forces were to be involved in the upcoming D-Day events, and it seemed more logistical planning was given to the commemoration than the original invasion. We were met by ranking officers of both the Air Force and the Army, and several Special Forces Rangers were assigned to our plane as jumpmasters. We took the Dakota up for a dry run over the drop zone while the Rangers inspected the static line and got a feel for the jump.

We had planned to fly back to England, but decided to laager in the port town of Le Havre, 50 miles north of Caen. The ramp at Le Havre included a B-17, a B-25, three C-47s, and two or three Mustangs. The assembled fleet of airplanes, including ours, would take part in a formation fly-over of the 15 heads of state, including President Bill Clinton and Queen Elizabeth II, who would take part in ceremonies June 6 at Omaha Beach.

———

I rented a Peugeot van somehow, hacking my way through the French language as if I were lost in a jungle. Most Europeans agree that the French are unbearably arrogant about their language, absolutely refusing to speak English — particularly to Americans. After about 20 seconds of being treated like a sloth, I decided that if there was such a thing as an Ugly American, I wanted to be one.For the next several days I terrorized both the French countryside and most of our guys as I drove with the intention of breaking any French traffic laws that might exist. It was like driving in Georgia, but with worse signs.

Still, we found our way around.

———

The most remarkable part of our adventure was the weather in Normandy on June 4. Almost duplicating the foreboding conditions that plagued Eisenhower's decision to invade, the ceiling hung low and dark. Winds with gusts to 40 or 50 knots blew cold rain in horizontal stilettos. If the weather didn't change, there would be no jump. Conditions set by the Army held that the ceilings must be high enough to put the jumpers out at 3,400 feet — no lower — and the surface winds could not exceed 13 knots.Late on the fourth, we had made our way to Colleville-sur-Mer, overlooking Omaha Beach at the site of the American Military Cemetery. With 9,986 marble markers, the cemetery is an inspiring place. We managed to talk our way into the cemetery at sundown, even though the U.S. Army had taken control of security for the ceremonies to be held there beginning the next day. As we were escorted across the sacred grounds by a lieutenant, the gray storm clouds broke and a brilliant sunset enveloped the bluffs and Omaha Beach below. Looking down on Omaha stunned me. How could anything get off that beach and up these hills? The rows of markers behind me provided the answer.

———

JUNE 5 dawned with bright sunshine and blue skies, dotted with occasional cumulus about 3,000 feet. The wicked weather of the night before had passed somehow, and the winds had quieted. There would be a jump today.We landed at Caen again, and before the door could open several of the D-Day veterans had gathered by the Dakota. They could not contain their excitement; we mingled together, introducing ourselves and talking about our trip.

An aroused contingent of the international press descended on the scene. The veterans were the big story for the day. Every sort of media hound sought photos or video as the veterans went through a rehearsal with the young jumpmasters.

———

For most of the veterans, the vibrations and sounds and smells of the Dakota brought back the past in a rush of emotion. George Yocum was a 22-year-old paratrooper of the 82nd Airborne in 1944. As he first climbed into our Dakota, I asked him when he was last aboard a C-47."Fifty years ago," he said in a voice edged with excitement.

"This is such an emotional feeling," he commented. "When we jumped, I was riding up there, at about the second window. As we stood up, our plane was hit and it threw me to the floor. We got up and the green light came on and we made it to the door. I found out later that our plane had crashed and the pilots were killed that night."

———

During the practice session, the 26 veterans who would jump from our Dakota were animated, clowning and joking with one another while the press swarmed around them. But when the time came to load up, chutes on, a somber mood prevailed.The jumpmasters had done their best to prepare the vets for the jump ahead. Sgt. Albert Dempsey, 34; Sgt. Carlos Sanchez, 35; and Capt. Dave Kanamine, 35, treated the veterans with respect while instructing them on the jump. When we were finally nearing the drop zone and the first stick of six vets stood to hook up, the younger members of the 82nd could not resist a few rousing shouts of "Airborne!"

———

I had the E-ticket. While Epps and Harless piloted the airplane, and Brooks and Hand sat up front, I was inches away from the open jump door. Sitting on a steel tool box along with Berndt Birkholz, the video cameraman, I was shooting still pictures with one hand and reaching over with the other to trip the shutter release for a remote camera I had mounted on the outside of the plane.

As each of the men moved to the door, they looked over their shoulders toward the jumpmaster. I couldn't help feeling a swell of pride for what these guys were doing. They were young men again, and the looks on their faces were cast from determination, laced with just a smidgen of fear. But they all went out the door.

———

During one pass over the DZ, Epps had cheated down on the altitude to stay clear of clouds. The jumpmasters waved off the next stick, so on the next circuit, Epps bore a hole through a couple of clouds to remain at 3,400 feet AGL. The jumpers were going to jump, no matter what.

———

Suddenly, the plane seemed empty. We'd done it; the airborne was out the door. The jumpmasters gathered around the door, straining to see open chutes.Epps circled the DZ a couple of times, lingering longer than the controllers below would have liked. He finally wheeled around toward Omaha Beach as 16 C-130s bore down on the DZ to drop a battalion of the 82nd and 101st Airborne.

———

The whole thing, of course, was immensely successful. Images of the veterans hurtling out of the Dakota were on every TV screen and newspaper around the world. But the limelight fell short of the Dakota. The story of how it had made it to France to complete its mission, in spite of the difficulties encountered, is known only to readers of this account.Brooks liked it that way. He brought the airplane to France to honor the memory of his father, who was an airman during the war, and to honor the efforts of the veterans who had worked so hard to make the jump happen. The emotional current that ran through the airplane was thanks enough.

On the ground, the media circus surrounded the veterans and their jump. But in the Dakota, on the way to the DZ, those old guys were by themselves. In each face there was a pitched look mixing pride with a little sadness. They had all done this 50 years ago, when the stakes were life or death. Most of their friends were lost, and it was for them that these men jumped again.

Mission accomplished.

———

Back at Caen, Madame Lemardis, the airport manager, was up to her old tricks. She had proven to be a source of irritation for colonels of several air forces. Now, just a few minutes after we had taken off from her airfield to drop our vets, she was refusing permission for us to land again at Caen."You must go to Cherbourg," the controller relayed hesitantly.

Epps was having none of it. "We must land at Caen," he told the tower. He asked that the military in the basement below be called. After all, we had our Victory call sign: we were part of the official events.

Standing in the tower, Madame Lemardis was adamant, and the controller refused clearance again.

Epps told him he was landing anyway. "I'll declare an emergency ... if necessary. Anyway, I'm downwind for 31. I'll call you on final."

As we made the last turn, the controller cleared us to land.

"You could hear her screaming at the top of her lungs in the background," laughed Brooks.

The jumpmasters helped load our gear back on the airplane in record time, as three gendarmes with machine guns walked up.

Sgt. Dempsey asked Harless if we needed anything else.

"Well, we may need you to whip those guys' asses," he said, nodding towards the policemen sent by Madame Lemardis.

"We can handle that, sir," snapped the Ranger, matter-of-factly.

———

THE following day we flew in wingtip formation with two other DC-3s over the American Military Cemetery at Colleville. Below, on the run into the shoreline, we passed over an armada of warships and vessels that had assembled to re-enact the D-Day flotilla. The great flight deck of the carrier U.S.S. George Washington slid directly beneath us as we flew at 400 feet across the heads of state gathered for the beachside ceremonies.

Returning to Georgia took a little longer without the favorable tailwinds of the trip over. Although the ride was slower, it was much less eventful — which is to say that the D-Day Dakota didn't require any more unscheduled engine changes in the field. And how will the next chapter read in the colorful history of Brooks' C-47? Only time can answer that question.

August 1994

Over fifty years ago, on July 15, 1942, history’s single largest forced landing of military aircraft left eight planes, two B-17Es, and six P-38Fs spread across a half-mile of the Greenland ice cap.

This story recounts the intrepid adventurers of The Greenland Expedition Society, and their incredible efforts to excavate a Lost Squadron P-38 from its resting place beneath 264 feet of ice.

———

Since 1981, Pat Epps has worked to find and recover the famed Lost Squadron. The ill-fated flight of two B-17E Flying Fortresses and six P-38F Lightnings bellied in on top of the Greenland ice cap on July 15, 1942.In late June of 1992, Pat invited me to join him and the Greenland Expedition Society on a journey to the Lost Squadron’s current resting place, located under 264 feet of glacial ice. I found the real story not in the airplanes, long lost and now found, but instead in the dedication of the expedition’s men and their determination to bring history to life.

"You know, you ought to let me go back up there with you," I said to Pat Epps. Pat was home from the Greenland ice cap for a few days, and I we were dicussing the progress his team was making in the retrieval of a P-38 from the Lost Squadron.

It was really just a rhetorical proposition.

“Okay,” he said. “I’ll pick you up Saturday."

Pat called on Thursday to confirm that I would accompany him, leaving me with a day to prepare for — well, I didn’t really know what to prepare for.

I started fretting immediately. I was supposed to be excited about such an adventure but, just between you and me, I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. I didn't want to charge off to the Arctic and lower myself down a 264-foot-deep shaft inside a moving glacier. I am not that intrepid; but the fat was in the fire. I couldn't gracefully bow out of this one.

The next day I went shopping for long underwear and wool socks.

———

The story of the Lost Squadron is well known to most of us in aviation. The airplanes were being ferried across the Atlantic in 1942 to join the war in Europe when they encountered bad weather. Low on fuel, they were forced down on the Greenland ice cap. The flight crews were rescued, but the aircraft were abandoned to the glacier.Enter Pat Epps, who owns Epps Aviation — the long-time FBO at Atlanta's DeKalb-Peachtree Airport — and his friend Richard Taylor, an Atlanta architect. After an impromptu Bonanza flight over the North Pole following Oshkosh in 1979, they decided to stop in Greenland on their return trip to Atlanta. It was on this trip that Epps and Taylor first learned of the Lost Squadron, and they resolved to undertake a search for the airplanes.

In 1981, the two adventurers launched a quest to find and retrieve the Lost Squadron with visions of flying the warbirds off the ice. Forming the Greenland Expedition Society, they spent the next decade traveling to the ice cap and pushing forward the technology needed for retrieval.

Somehow, I was lucky enough to witness it.

Off we go

The Navajo Chieftain rolled onto the ramp at Johnston County Airport on time for the long trip to Greenland.

Pat popped out the plane along with Gary Larkins and T.K. Mohr, two aircraft recovery specialists from out west. Gary and T.K. were called in to bring a P-38 from its resting place beneath 264 feet of ice.

The Navajo looked like a freight hauler, loaded to the gills with everything from toolboxes and sleeping bags to Bisquick and Oreos.

We took off for Montgomery County Airport in Gaithersburg, Md., where we would stop for fuel, lunch, and a satellite telephone that would add another 80 pounds to the cargo. On the way up I started plugging lat/longs into the Trimble GPS unit I'd brought along. The impact of where I was headed started to sink in as I programmed waypoints for places with names like Goose Bay, Nuujuaq, Godthab, Sondre Stromfjord, Narsarsuaq, and Kulusuk. And Tomcat Site 65 deg.18 min. N by 40 deg. 04 min. W -- on the Greenland ice cap, where eight 50-year-old airplanes lay beneath the ice.

———

I flew right seat on the leg to Quebec, where we cleared Canadian customs. It was summertime-hot in Maryland, and we were on a 4,000-foot runway aiming for huge power lines at the end."I want to weigh this stuff," Pat said with a twinkle in his eye, "but right now I don't want to know."

We made it off the runway and, as a bonus, over the power lines.

I punched our route into the GPS: Direct Quebec. VFR.

Airplane pirates

Errol Flynn is alive and well in the person of Gary R. Larkins. Larkins, 41, from Auburn, Calif., is an aviation buccaneer, pulling lost warbirds from the ocean floor and from jungles around the world. Over the last 20 years, he has salvaged 49 airplanes. As Director of Recoveries for the Institute of Aeronautical Archaeological Research, a Sacramento-based salvage and restoration firm, Larkins had just come from three months in the mountains of New Guinea, where he and his team had retrieved another P-38 that had crashed during the Big War. In the 100-degree-plus weather there, he slept on the wreck's wing because there were too many snakes in the elephant grass below.

Larkins has piloted most of the exotic warbirds you can think of, including PBYs. Our Arctic adventure was just the right venue for this swashbuckling airplane pirate.

———

I decided to become an airplane pirate myself, and Gary agreed to take me on as his apprentice. When we landed in Quebec, Pat knew the Customs officer and we didn't even have to show our passports. But I wanted mine stamped, and while Gary and I sat in the customs office lounge, I saw a different inspector and asked him to do the honors.Naturally, my foot-in-mouth disease reared its ugly head again, as the Customs agent asked about my lack of proper forms. He finally gave up on us and walked away.

Gary looked at me and said with mock seriousness, "Rule number one: Never talk to Customs." I was on my way to piratehood.

———

Thomas K. Mohr, 60 — he goes by T.K. — grinned at me. "I heard they were 80 feet under ice," he said. “Then I found out they were 80 meters under."T.K. is a 10,000-hour pilot, ATP rated in just about every old transport: DC-3, -4, -6, -7, Convairs, B-25 and B-26, jets like T-33 and F-86 and—important for this trip—P-38. He works as an A&P/AI for Western International Aviation in Tucson, right off the end of the runway of Davis-Monthan AFB, where he refurbishes and rebuilds aircraft that are often warbirds. He’s done a lot of crazy things over the years, including crashing airplanes as a lead pilot on firebombers.

But this trip is something altogether new. He is excited to be part of such a historical moment: “I wonder how, out of all the mechanics in the country, I was picked."

———

We landed at Goose Bay, Labrador, at dusk with brilliant approach lights contrasting the darkening sky. We had logged more than 10 hours in the Navajo.We spent the night at the Ambassador Hotel, a steel building with comfortable rooms. I knew it was the last motel room I’d see for some time.

Goose Bay is a NATO training base. The next morning, U.S. Air Force F-16s, British Tornadoes, and Canadian C/F 18s were taking off with afterburners aglow. Pat received a thorough briefing at the Canadian Forces weather facility, while Gary and T.K. found a Canadian maintenance officer who provided them with what amounted to a treasure map: a list of crashes in Labrador over the last 40 years. Hurricanes, B-25s, B-17s, everything — along with site coordinates and status. Larkins licked his chops over the booty, and I could tell he'd be back to Canada to hunt for some of these other downed warbirds.

During the night an Aeroflot freighter had landed. Four of the crew jumped ship and asked for asylum.

This was a strange and wonderful trip.

North to Narsarsuaq

Greenland is a hard place to get to. Consider that the island, almost big enough to be a continent, lies above 60 degrees latitude. It's more than 2,500 miles north of Atlanta. Most of the 50,000 people who populate the island live on its western shoreline in Godthab, the capital, or farther north in Sondre Stromfjord.

We would make landfall and stop for fuel on the southern tip of Greenland at Narsarsuaq. Our destination was the desolate and remote east coast, a landing site called Kulusuk.

North Atlantic weather is a cauldron of unpredictability. We expected poor conditions for our 5 1/2-hour flight across to Narsarsuaq and Pat prepared alternatives to fly a more northerly route to Godthab.

With about 6 1/2 hours of fuel on board, there wasn't much room for error. We had a four-man raft and life jackets. But there were no immersion suits — the bulky, thermal wetsuits most ferry pilots wear when they fly across. In North Atlantic waters, you might last 30 or 40 seconds before hypothermia gets you. Immersion suits can prolong that to a few hours.

I accepted the fact that if we bit the big one on this leg and had to ditch, we were all ice cubes. After all, immersion suits are really just body bags with face openings. Larkins put the entire exercise into perspective for me: "Why stop living," he mused, "just to stay alive?"

But the ominous weather forecast the night before didn't come to pass. When we broke out on top at 7,500 feet, climbing to a cruise altitude of 9,000, everyone relaxed and settled in for the long flight. Occasionally, a break in the undercast gave us glimpses of the ocean and a smattering of icebergs.

.jpg)

———

Clear skies prevailed over the southern coast of Greenland. The near-continent rises sharply out of the ocean, its rugged coastal ranges a sheer barrier to seaward approach.We flew low across the ocean, picking our way through the myriad icebergs and ice floes dotting the water close to land. The summer thaw had loosed the ice pack to drift south, and we skimmed just above chunks big enough to land on.

The flight was a panorama of spectacular scenery as we flew up a fjord to Narsarsuaq. 50 years earlier, the Lost Squadron had tried to return here, a landing site then known as BW-1. Even now it is little more than a runway and small terminal building. The four of us were ecstatic to land there, our sense of adventure heightened by our arrival at such an isolated location.

After 5 1/2 hours, we were also greatly relieved to find excellent Danish plumbing fixtures available.

There are no customs to clear in Greenland. They must figure that if you made it this far, you don't need any extra hassles. The tower operator doubled as our weather briefer. Conditions were good for the three-hour flight north to Kulusuk, and after topping up with $1-per-liter avgas, we were off again.

———

The jagged mountains are absolutely sheared away by these omnipresent glaciers. There is no other abrasive force to erode and mold the shapes of the rock but the massive, inexorable movement of the ice heading out to sea.

The voluminous scope of the ice cap — and our relative insignificance — became clear. No help is available to an airplane flying in this region. With radio communications spotty, the feeling of isolation intensified.

The Kulusuk Hilton

On the way into Kulusuk, Pat flew low over Tomcat Base — the site of the expedition camp, named after the fateful flights of 50 years past. We couldn't land the Navajo on the soft summer snow at the site; that would be left for the expedition's DC-3 on skis. The camp depends on the Gooney Bird for heavy resupply, while a twin Dornier, also on skis, makes more frequent trips to the site.

We buzzed the camp several times as the expedition crew below waved excitedly. I looked down on the camp. A row of yellow tents, a tall flagpole with Old Glory waving proudly, and — for as far as the eye could see — snow and ice.

"No way," I thought out loud, "No way am I staying out here!"

———

These days it's more of a travelers’ way station, its old barracks providing modest overnight accommodations. The mess hall functions as a social center for the hardy group that maintains the airstrip, and provides basic services for the world’s most intrepid tourists.

It is also the staging base for the expedition, where the red-and-gold DC-3 laagers along with the Dornier used to ferry supplies out to Tomcat.

The guys on the expedition call the building the Kulusuk Hilton, and I’d know why before I left Greenland.

———

Oyvid, the man who runs Kulusuk, knew we were coming. He kept the mess hall open and, after nine hours in the Chieftain, we were treated to an excellent fried chicken dinner. As new travelers we caused a buzz of activity, and the mess stayed buzzing late with conversation and a few shots of spirits.———

About a mile from Kulusuk, down a snow-covered path and over a hill, the village of Capdan is home to about 400 Innuit people, native Eskimos. The road was still impassable to vehicles in late June. A couple of us decided to walk over, trudging through the melting snow.The village's wooden plank houses, painted brightly with blues, reds, and yellows, provided a colorful escape from the stark white landscape.

Another lesson in perspective waited for me over the hill. Life at its simplest: Wake up, fish, clean the fish, cook the fish, eat the fish, go to sleep. I walked past the dogsleds and wondered how people lived in such isolation, so far away from the rest of the world. But the people I saw and spoke to had smiles on their faces, and the children playing tag laughed gaily. Pat found a small outcropping of rock to sit on and looked out over the frozen inlet at the fjord and mountains beyond. It was midnight, and the sun was still edging over the horizon.

———

That first night of daylight was weird, to say the least. It just didn't get dark, and my body couldn't figure it out. If it ain't dark, it ain't bedtime.I did finally fall asleep, for about three restless hours. Then it was time to go to the ice cap.

On to Tomcat

The trip out to Tomcat, 125 miles south-southwest of Kulusuk, was also a re-supply mission. We worked up a sweat loading and securing 16 drums of Jet A and avgas on the DC-3. The big tailwheel left the cargo floor tilting at an angle, and much grunting was required to roll the heavy drums up the fuselage and turn them upright. The fuel kept the camp generators and equipment running.

We also had the load of provisions we had brought from the States, including fresh meat and vegetables. Outside the cargo hold, Pat and T.K. swept over the old airplane, preflighting, pouring buckets of oil into the round engines.

The Gooney Bird was heavy, but nevertheless lifted smartly away from the runway. It was my first ride in a DC-3, and I was bent over behind Pat, peering wide-eyed out of the pillbox windscreen.

The DC-3 had been a C-47 for most of its life. The 1946 airplane, owned by Don Brooks of Douglas, Ga., and on loan to the expedition, was converted to a DC-3 in 1986 by Basler Aviation in Oshkosh. The cockpit was a juxtaposition of ancient flight controls and modern avionics. A battery of old switches mixed with color radar and a loran on the refurbished panel.

T.K. flew as Pat's co-pilot. Pat, who had flown for 20 of the last 36 hours, nodded off to sleep. This just wasn't as exciting for him as it was for me.

———

He woke up in time to see Tomcat come into sight. The DC-3 swung around in a wide arc and lined up with a "runway" defined by flags.The big skis settled lightly on the ice. It wasn't like a crash, but it wasn't like a landing either. The airplane undulated slowly with the firmness of the snow and the Gooney Bird grudgingly stopped, robbed of momentum. We were abeam the camp as the guys gathered to greet us.

This was a high point for everyone. The Gooney Bird's landing interrupted the daily toil of routine camp life, and new visitors meant news and new conversation to the men who had been on the ice since May.

I jumped down from the cargo door and sank up to my knees in snow. I was relieved to know I had brought the right gear: Heavy, insulated rubber boots and waterproof pant shells. I looked around me, my eyes adjusting to the brilliant white reflecting from the snow. There was nothing but snow.

I heard Dorothy saying, "You're not in Kansas any more."

Then the work started. We unloaded the provisions and the drums of fuel. A Ski-Doo snowmobile dragged the supplies away on pallets.

I felt as if I had stepped into a photo from National Geographic.

In fact, I had.

Down The Hole

The first order of business once we emptied the plane was getting a look at The Hole. Over the past weeks, the crew had worked to melt a shaft down to P-38 Delta, the aircraft believed to be in the best shape following its forced landing.

My first glimpse of the shaft left me shocked. How could these guys come out here and make this incredible hole 264 feet into the bowels of the glacier?

A small bulkhead, two feet high, served as a guard to the edge of the hole. The hole had been widened to about four feet by eight feet using the Super Gopher, a mole-like device that uses hot water to melt a path through the ice.

I cautiously peeked over the edge, into a bottomless, black pit. I stood back and shook my head woefully. "I am not going down that," I said out loud.

It had been decided that I would go down the hole right away so I could photograph the Lightning before it was further disassembled. Various cowlings and panels had been removed and brought up, as had the four .50 caliber machine guns and the six-foot-long 20 mm cannon. Earlier I had watched as Pat and Gary were lowered into the hole. I noted the apprehension that flushed across Gary's face. This guy was used to doing dumb, dangerous things, but even he took stock of the risk.

Now it was my turn. Hey, I did not want to go down there — I am not that brave a guy. Really, I'm not. But here I was, on the ice cap, in front of God and 12 hardy souls. I knew there was no clever way to weasel out of this. (I know some of you think that you'd just love the chance to go down the hole, but no mortal can stand above it without some serious thoughts about home, family, and insurance policies.)

I would go on the chain hoist first, then Gary. Gordon Scott, the Hole Master, would escort us down.

Bob Cardin, the expedition's leader, helped me dress out for the descent and gave me instructions. The bench seat is like the one used by miners, and I snugged into it. A safety harness was cinched tightly round my waist.

I had put my camera equipment in zip-lock plastic bags and wore a raincoat. A hard hat with a miner's light completed the ensemble. I clicked the harness ring to the chain hook and attached to a dead-man safety rope using a Jumar safety device.

The long ride down takes about 20 minutes on the chain hoist.

I swung my feet over the edge of the low bulkhead. Most everybody in camp had crowded into the operations tent to watch as the new meat was suspended over the chasm, dangling above the 264-foot shaft to hell.

I looked up at the faces grinning down at me and yelled, "This is the most stupid f--kin' thing I have ever done!”

I meant it, too.

The ride down

As we were lowered, the whir of the hoist and the noise of the generators diminished and was swallowed by the shaft. The silence was disconcerting at first, but then a surreal calm prevailed.

The sides of the shaft were mostly smooth from the path of the Super Gopher, but the evidence of the years was still clear. Alternately, swaths of snow from winters and melted ice from summers showed through the walls. There are lights about every 75 feet down the shaft; the ice was pale blue and clear.

A bundle of electric wires was strung down the side of the hole, and a large fire hose reached to the bottom to remove melted water.

Gordon carried a handheld radio strapped to his chest. The support crew above occasionally asked for a radio check. "Ops normal," he would respond.

I stared at the wall of the shaft, and remembered to breathe.

About 80 feet down, a piece of plywood jutted from the wall. It was left over the shaft during the 1989 expedition, and marked the depth of the attempt to reach the P-38 that year.

A little farther down, we passed the Firn Line, the level of the water table inside the glacier. It began to rain down the hole as water wept from the ice.

Ten feet above me, Gary sang a cowboy song. I considered my unique circumstances, one of maybe 30 people on earth to have been inside an arctic glacier.

———

The airplane rests on a bed of ice. The big hole empties directly above the number two engine, which provided a sturdy landing spot for us.Happy to make it down, I was hardly prepared for the sight that greeted me. A 50-foot-long cavern had been melted around the plane. The opening in the ice resembled melted Styrofoam. The crew had used a homemade water cannon, a device with a fire hose nozzle that sprayed hot water to melt the ice, carving out the work space.

In most places you could stand up. Walking was precarious, but spikes attached to our boots held our footing. Halogen lights had been erected, casting an eerie glow on the cavern ceilings, shadows giving texture to the walls. The air was heavy and wet. The temperature in the cavern, constant at about 30 degrees Fahrenheit, was comfortable as we moved around working.

The airplane lay on its belly, its twin tail booms disappearing into small openings in the ice. The airplane is in great shape. A P-38F model, serial number 417630. Though there is skin damage from the weight of the ice, it is structurally sound. In fact, the whole crew received a big morale boost when Gary came out of the hole the first day and proclaimed the airplane in excellent restorable condition.

The tail assembly had been pulled about 15 feet away from the tail booms – and the rest of the airplane – by the glacier. The canopy was crushed, but the cockpit itself was fine. Compared to other warbird restoration projects, this airplane is a rare jewel. All original, brand new parts. Fifty-hour Allison V-12 engines. No corrosion anywhere.

As Gordon set up additional work lighting, Gary went straight to work disassembling the number two engine. He was amazed at the condition of the parts. He was able to unscrew bolts and fasteners as if he were in a hangar. The aircraft offered no resistance to the work. Glycol and oil were still in the lines and hoses.

The plan was to remove the engines, props, tail boom, and wingtips and hoist them to the surface. The center section of the fuselage would present the biggest challenge: the aluminum main wing spar stretched 17 feet across from the outsides of the two engines. The hole would have to be enlarged somewhat to accommodate it.

———

I eased myself into the cockpit of the new, 50-year-old fighter. I tried to imagine the feelings of the pilot who emerged from this cockpit so long ago. It's a small cockpit, cramped with gauges and instruments. The instrumentation was in pretty good condition, though a little dirty and worn. The canopy had been crushed by the weight of the ice, but overall the sight was remarkable. Placards still gave instructions for the landing gear, throttle levers were retarded and props pulled to feather.I squeezed my feet into position on the rudder pedals. This thing is built for speed, not comfort.

I sat there, incredulous.

———

I stayed down in the hole more than three hours before heading up the shaft. The return trip was more enjoyable, my earlier fear and worry replaced by a great sense of glee and satisfaction.From then on, the work continued through two eight-hour shifts each day, with three guys going down at a time to finish taking the airplane apart.

What makes the effort so remarkable is the industriousness of the expedition members. Every needed item, if it wasn't brought along, had to be fabricated. A solution to every problem was devised with good old Yankee ingenuity. If a glitch cropped up, it had to be dealt with from existing resources — there is no corner hardware store on the ice cap.

Camp life

Bob Cardin is the expedition manager and the man charged with bringing the airplane to the surface. Retired as a lieutenant colonel from the U.S. Army, he was an army aviator and airfield commander.

He is completely focused on his purpose at Tomcat. "They told me to bring up an airplane, and that's what I'm going to do," he said stoically. "Even if I have to cut it into four-inch pieces with my pocket knife."

Bob is a tremendous leader. He analyzes every member of his team, and plays to each one's strengths while minimizing each man's weaknesses.

He also snores pretty damned loud.

———

I bunked with Bob Cardin and Bart Wilder. The tent had a kerosene heater that knocked the edge off the cold. The last night I was there, the outside temperature dipped to 12 degrees — but inside it was a toasty 28. I slept in an arctic mummy bag. By my second night on the cap, I decided I could sleep anywhere.

Dave Kauffman is a mechanical engineer from Atlanta. He had taken a leave of absence from his job to be part of the expedition. When I met him he had been on the ice cap for 56 days. Dave, along with John Fogarty, an electrical engineer also from Atlanta, helped me stow my gear in a tent and showed me around the camp when I arrived.

The camp consists of a row of four expedition tents for living, a supply tent, the mess tent and three tents for operations: Two for mechanical equipment and the third, larger one covering the hole over the P-38.

The tents were nearly below the surface, the result of more than 12 feet of snow the site had received since the expedition arrived May 6. "Our motto is 'Shovel or Die,'" Dave smiled.

———

About 300 yards south of the camp, a large hole had been excavated in the snow. At the bottom, ice steps led down to a small opening — the operations tent from the 1990 expedition that had reached the B-17 "Big Stoop."That year had resulted in disappointment when "Big Stoop" was found to be badly damaged. Still, the expedition had proven that it could reach under the ice and touch the planes. A steel I-beam from the '90 effort kept the inside of the tent intact under the 35 feet of snow that had accumulated in two years. The team was able to retrieve a lot of useful equipment, including some generators and hoists, to use this year.

They also uncovered the diesel skid-steer loader they'd left behind in '90. It had rested quietly for two years in the cold, but when they hooked up its battery the engine cranked to life on the first try.

———

Lunchtime the first day was my introduction to the mess tent. It is the social center for expedition members. Inside, it's always warm from the kerosene heater and there is a perpetually-full coffee pot.The sign above the entrance purveyed a double entendre. "Putting fire in the Hole," it reads. In addition to serving three meals a day, the mess is also where off-the-clock members gather to write in their journals or listen to the BBC over shortwave radio. Twice each day, a ham operator in Maine reaches the camp over the airwaves to bring news and pass on messages from the expeditioners.

———

I would soon know all about the mess tent. I volunteered to relieve the camp's cook, Lou Sapienza. For a day and a half, I became part of the expedition instead of a mere observer. In fact, I had a new vocation: Arctic Pot Scrubber. I did become popular after my first lunch, a kind of beef stroganoff number with pan gravy and scratch biscuits. They liked it enough that they threatened to kidnap me, making me cook for the duration of the summer."We don't waste anything on the ice cap," I was told, so I started a two-gallon project of soup du jour. T.K. was my soup content advisor. He called the creation "Sonofabitch Soup," for when you tasted it you'd say, "Son of a bitch, that's good!”

Over the next couple of days the soup took on new character as its contents grew and simmered. One night after dinner, instead of raking the plates into the trash, I had all of them scrape their plates directly into the pot.

Waste not, want not.

———

Gordon Scott, 42, a ranking member of the expedition, is a veteran of the '89 and '90 efforts. A tall, rough-hewn man from Girdwood, Alaska, he came to the Greenland Expedition Society through his association with Col. Norman D. Vaughan.Vaughan, now in his eighties, was the last man to have seen the Lost Squadron when, as an Army major in 1942, he dogsledded alone to the landing site and retrieved the secret Norden bombsights from the downed B-17s. Vaughan had been with Adm. Richard E. Byrd on the famous 1928-30 expedition to Antarctica.

———

The necessary facilities for man's bodily functions were located about 20 yards downwind from the camp. An outhouse with an open front faced south, and from the royal perch you could look across the ice at the ocean 20 miles away. A pole with a flag had been erected as a signal. If the flag was flying, the can was in use.It was a challenge, to say the least, to bare all in anticipation of the moment of contact with the seat. This was not a place to loiter. Business was dispatched quickly. We'll call it a lesson in perspective.

———

Bart Wilder, 21, lives in Macon, Ga. Sam Knaub, 29, is from York, Pa. Both are former U.S. Army Rangers and capable of putting up with any hardship. They are also both A&P mechanics, and between playing practical jokes on one another they’d help dismantle the airplane. Jorn Skyrud, 25, is from Oslo. The Norwegian did his pilot training in Conway, S.C. As a member of the expedition, he is most comfortable with the nordic conditions.Another face is Tony Pope, 31, from Douglas, Ga. Tony is a paramedic and provided medical expertise in such a remote location. He came prepared, stocking IVs, splints, suture sets, oxygen, and antibiotics. "Everything you'd find on an ambulance," he said.

The expedition's physician, Dr. Dan Callahan, would be on the ice soon, along with other long-time expeditioners such as Norman Vaughan and Richard Taylor, Epps' partner in the whole affair.

Some of the expedition's critical members had gone into Kulusuk while I was on the cap. Neil Estes and Weegee Smith are both senior members of the effort with whom I spent little time, but had been working for two months.

———

The midnight sun confounds one's senses, and the fatigue of the 20-hour days showed on the faces of all the men.There were moments of great levity. Gary had brought along a three-iron and some fluorescent red golf balls. We had a great time on our impromptu driving range, playing the first Arctic Open.

Homeward bound

I made my way back by catching the Dornier to Kulusuk. The expedition supply pilot is an Icelandic native who goes by the monicker Iceman. On the way back he let me fly the Dornier. We flew low, sometimes 20 feet over the ground, skirting chunks of ice and looking for seals. When I got to Kulusuk, I learned why the modest barracks had earned the nickname Hilton. The musty shower stalls of a few days before had become a luxury of delirious proportion in comparison with the camp.

I threw on the first clean clothes I had worn in four days, and barely made a Jetstream that was leaving for Reykjavik, Iceland. The next day, I caught an Icelandair 757 back to Baltimore.

———

It was the trip of a lifetime for me. But I was only a visitor for a few days. The guys on the ice landed there May 6. They had built a city, conquered the climate, and achieved an incredible feat, making their way down through 264 feet of ice to bring history to the surface and light of a new decade.

But the men of the Greenland Expedition Society have faced a lifestyle of harsh weather, little sleep, and difficult work under poor conditions. Their stalwart dedication to the task is what makes the story of the Lost Squadron.

And history will add another chapter through the spirit of adventure, determination, and achievement of the expedition members.

August 1992

With the runway at Seymour Johnson AFB falling away, an F-15E climbs with a maximum performance takeoff. The fighter will reach 10,000 feet in just over 20 seconds. It takes a Cessna 182 about 20 minutes to do the same.

Here's what you need to know about flying in the same patch of sky as the fast burners.

———

The peace of such scenic flights belies the vigilance that pilots like me should have. The regular obstacles to safe flights at low altitudes are clear — towers, birds, and bad engines among the items to avoid. But another marker on a low flyer's checklist had better include knowledge of other low-flying traffic.

Take a look at any sectional chart depicting the southeastern United States, and you'll find large swaths of airspace carved out for use by the military. This Special Use Airspace — Military Operating Areas, Restricted Areas, and Prohibited Areas — provide identifiable zones where fast-moving fighters and low-flying transports are likely to be found.

What most general aviation pilots may find surprising, however, is that much of the flying done by the military is not necessarily contained to these areas. Low-level training routes, both for VFR and IFR conditions, crisscross the landscape. The Visual Routes, or VRs, take military pilots and their fighters along the nap of the earth — usually below 1,500 feet AG and at speeds that nearly reach the sound barrier.

———

WHILE zipping along the proscribed lanes of these routes, military pilots are usually on their own and, just like the guy plugging away at 500 feet in a Cessna 172, they are not talking to air traffic controllers. The fast burner may see the bug-smasher on an air-to-air radar display, but the special demands of operating a fighter so close to the earth and at such high speeds allow no guarantee that a general aviation target will be safely avoided.

The combination of fast-flying military jets and slow-flying general aviation airplanes provides the backdrop for a potentially dangerous mixture. Understanding how the military use low-level training routes can give general aviation pilots crucial safety information for flying near said routes. To find out how the world unwinds from the fighter jockey's seat, I recently went along for the ultimate joyride. In the back seat of a McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle, I flew a low-level mission through the mountain valleys of West Virginia and Virginia with the 335th Fighter Squadron — the famed Chiefs of the U.S. Air Force's 4th Wing based at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, N.C.

———

I flew with Major Rob Hampton — known as "Hampy" around the squadron — who is the assistant operations officer of the 335th Fighter Squadron and the number three man in the Chiefs. His square frame could be that of a tradesman, but Hampton flies the F-15E for a living. As he moves through the squadron building, junior officers pay him a respect that is borne from more than his high rank. Hampton is gregarious, but carries a solid confidence and command authority.Hampton came into the Air Force through the ROTC program at Daniel Webster College in Nashua, N.H., in 1983. He underwent his initial pilot training at Shepherd AFB in Texas before heading to England to fly A-10s at RAF Woodbridge. He spent several years as an instructor pilot in T-38s at Columbus AFB in Mississippi before transitioning to the ultimate airplane in the air force's inventory: the F-15E at Seymour Johnson.

———

"I was a standard kid on the airport fence when I was growing up," Hampton recalls. "My uncle started my flying when I was eight. I saved every penny I made when I was a kid, cutting grass, doing anything, shoveling snow in the wintertime. When I turned 16 I had, like, $2,300 in the bank. I spent a year in Sweden, but when I got back I walked into the FBO and said, 'Here's my money, teach me to fly.’ It's all I have ever wanted to do,” he remembers. Now 35 years old with more than 3,000 hours in A-10s, T-38s, and F-15Es, Hampton enjoys nothing more than taking his 16-year-old son flying in rented airplanes. "We go up and putt around. I give him the controls and I sit there and watch," he says. "It's a kick."———

CAPTAIN Doc Watson is a weapon systems officer — a WSO, or "wizzo" — who flew into combat in the back seats of F-15Es during the Gulf War. He took me through the survival training facility at Seymour Johnson, teaching me how to get out of a bird gone bad.The egress training was pretty straightforward. If the pilot decides that it is time to leave the airplane and he pulls the ejection handles, you are going to leave the airplane. The ACES II ejection seat in the Strike Eagle takes all of 1.7 seconds to blow the canopy, eject the backseater, and then release the pilot. Rockets in the ejection seat generate a 15-G ride that puts the occupant’s survival in the seat designers’ hands. The seat is a sophisticated piece of hardware with pitot tubes and a static port, enabling the chair to determine when to deploy the pilot's parachute and cut itself away. The seat won't deploy the chutes until it reaches the relatively safe altitude of 14,000 feet — survivable if you happen to be unconscious.

If the frontseater becomes incapacitated, the chairs can be fired from the back. I knew I would never have the nerve to switch the ejection control knob to manual and pull the black and yellow seat handles. But now, at least, I knew how to do it. I spent some time looking at a big chart on the wall. Slow to 250 knots, try to maintain altitude between 5,000 and 10,000 feet, "bail out, bail out, bail out."

The survival equipment that is attached to the parachute ensemble weighs in at 23 pounds, and has everything you need to survive except for the bugs.

On the ground, the seats have a zero-zero capability — zero altitude, zero airspeed — that will send the seats high enough for the chutes to open. If an on-ground emergency exists, the words "egress, egress, egress" are commanded. What that means is, "Let's get the hell out of here!” — a rapid exit of the airplane and its environs are in order.

———

Our sortie of two F-15Es, call signs Arrow 41 and Arrow 42, would consist of Hampton and me in the lead and Major Al Botine, an experienced combat pilot, flying the wing position with Captain Dennis Schell as his backseater.Schell had been out of the cockpit for several months, and needed a low-intensity mission in the Eagle before resuming his regular flying rotation in the jet. Schell prepared the route briefings for the flight, carefully detailing the information that would be programmed into the fighters’ inertial navigation system.

The Eagle's INS is a Litton ring laser gyro. Three spools of fiber optic line carry beams of lasers over a long enough distance to measure changes in the light’s frequency shift as it accelerates or slows across three dimensions. Computers calculate the distance traveled since programming jet’s INS with the coordinates of its ramp parking space prior to taxiing for takeoff.

The Eagle's INS is the most sophisticated in the world of fighter aircraft, and gives the fighter complete autonomy in navigation. After a sortie that covers 600 or 700 miles, the INS is usually no more than a half-mile out of register. Though not as accurate as a Global Positioning System, the independence from outside electronic jamming or other interference gives the F-15E unmatched wartime capability.

———

The plan Schell prepared was to depart Seymour Johnson and climb to a cruising altitude of 18,000 feet. I would not be going over water or above flight level 180 because I hadn't had water survival or high altitude training.Instead, we headed northwest to West Virginia, where we would drop out of the sky to join VR-1758. The Visual Route followed mountain valleys, ripping and tearing across ridge lines and down riverbeds.

Schell had picked a few targets for us to find, including a railroad tunnel burrowed into a mountainside. We would do a few special exercises along the route, then climb out for the trip back to Goldsboro. Back home, we’d enter the Echo MOA for some air work and individual "acro" before rejoining to land.

———

THE preparations for the flight included the spectacle of dressing a short, dumpy guy like a fighter pilot. After break dancing into the flight suit and enduring the sausage-like encasement ritual of zipping into the G-suit, I felt ridiculously juxtaposed next to the jet pilots.Nevertheless, I sucked in as much gut as I could, and did my best Tom Cruise impersonation when it came time to step out to the flight line. Then, finally strapped into the jet, I began to feel the claustrophobia of the full flight suit, as its bulky helmet and restricting oxygen mask bore down upon me.